Scorecard (November 2025)

Acquired assets with a combined value exceeding £500 million since founding V7

Managed £400 million of capital expenditure projects across the UK

Let over 350,000 sq ft of office space

Secured planning consents totalling more than 575,000 sq ft

Career overview

V7 – Co-Founder & Director (2015–Present)

Legal & General Investment Management – Senior Asset Manager (2013–2015)

Cushman & Wakefield – Associate, Business Space Investment (2012–2013)

Cushman & Wakefield – Associate, Thames Valley Office Agency (2005–2011)

Notes from our interview

We sweat assets as hard as you can possibly imagine, but only a small number so we can add true value.

For every investor we've completed a project for, we've had a repeat project. Every single one. If that ever breaks, I'll be devastated.

We've had internal debates about whether you can succeed by being humble and reliable, or whether you have to be aggressive and cutthroat. We've chosen the former. And it seems to work.

We thought we were ultra-specialists. One sector. That was our edge. Then Covid hit and we were too concentrated. The answer wasn't to go broad - it was to diversify where it made sense.

We run two separate companies: V7 Office and V7 Industrial - different directors, different teams. That way we keep our depth but still grow across sectors.

For the first few years, we bought deal by deal which felt scattergun. Now we pre-agree a strategy and deploy. If it doesn't fit the strategy, we don't look at it.

Give us your two trickiest buildings, the ones giving your asset managers headaches. We'll sweat them, sort them, and hand them back when they're dry.

We try to understand our buildings better than anyone by building relationships on the ground, right down to the front-of-house and site teams.

I drew a chart years ago on a piece of paper: leasing, investment, asset management, my own business. I stuck it on my fridge. Ten years later, it happened almost exactly as planned

You've got to know where you're going. Otherwise you drift.

It must be something about mobile phones as a first job. First Nigel Henry, now Chris. Both started out selling them before finding their way into development.

After selling phones, Chris went into recruitment. But property was always around him. His dad was an architect, his mom a conveyancing lawyer. “I decided I wanted to do up a house, so I wrote my dad a business plan. I said, can you lend me the money? I’ve found a house, I want to split it into three flats, I’ll find the debt for the rest, carry out the works, and then I’ll become a developer.”

His dad agreed, but only formally. “He lent me the money with a loan agreement in place, as if he was one of my investors.” Chris bought the house, ripped it apart with a few friends, turned it into three flats, sold it, paid his dad back with interest, and used the profit to fund a master’s in real estate.

He thought it would be about houses. “I turned up on day one and realised it was all about commercial. I thought, oh my God, I’m in the wrong place. But I stuck it out, and I’m glad I did, because I’ve been commercial ever since.”

Leaving the desk

After a few years at Cushman & Wakefield, Chris joined Legal & General. He learned the institutional side, asset management, fund reporting, process. “It was brilliant experience, but when you work for a fast growing fund, you’re spread so thin. You’ve got so many assets to look after, I didn’t actually get to visit them. I was sat behind a desk struggling to make time for inspections. You’re apparently in real estate, but I didn’t actually see the buildings as much as I needed or wanted to.”

He realised what he missed: buildings, people, place. “I love architecture, I love design, I love communities. And when you’re in that kind of role, you don’t really have the time to do that.”

One night, sat in a pub with friends, he said it out loud: I don’t get to see buildings anymore. That’s when the idea for V7 started.

Soon after, he met Zak Veasey. “I’ve rarely met someone who talks as much as me but Zak talks more than I do. We both had the same passion for design, repositioning buildings and for working closely on a small number of projects. We didn’t want to be spread that thinly.” They talked for six hours straight and decided to join forces.

“We said we’d sweat assets as hard as you can possibly imagine, but only a small number so we can add true value. The goal was to be able to hand a building back once it’s dry, knowing we’ve done absolutely everything possible.”

That became the model:

do fewer buildings, but do them properly

squeeze every pip of value

know every detail, from service charge to marketing

They built a company around that. “We try to understand our buildings better than anyone by building relationships on the ground, right down to the front-of-house and site teams.”

Each DM/AM manages no more than three projects at a time. Some have two, some have one, but never four. You can’t do the job properly if you’re juggling. The whole point is to get under the skin of a building.

Building the firm

The idea was one thing; turning it into a business was another.

When V7 started, Chris and Zak spent six months pitching to every institution in London. “M&G, Aviva, L&G, Schroders, you name it. Everyone said, great idea, guys. But no one gave us any assets.”

Their pitch was simple. They weren’t chasing acquisitions; they were offering to reposition the assets the institutions already owned. “We said, give us your two trickiest buildings, the ones giving your asset managers headaches. We’ll sweat them, sort them, and hand them back when they’re dry.”

It was a good idea but the response was always the same. “They told us, we can’t give you anything because we have asset managers that should be doing that job.”

For six months, nothing landed. “It was definitely concerning, everyone loved the idea, no one wanted to be first.” So they went smaller. “We started working with the smaller funds, individual mandates, the people without the luxury of big teams. They were drowning in work, and we could help take the pressure off.”

The first projects involved rolling up their sleeves. They took on the hardest assets: small, regional, unloved offices. Stuff no one wanted. “It was proper grassroots. We worked on challenging buildings, made them better, and proved we could add value.” And then it snowballed, by working hard and doing a thorough job, they got the next one. Then another, there was no magic investor or lucky break. Just hard work. Chris takes pride in a particular statistic. “For every investor we’ve completed a project for, we’ve had a repeat project, Every single one. If that ever breaks, I’ll be devastated.”

Their approach to relationships is the same as their buildings, detail, honesty, consistency. “We’ve had internal debates about whether you can succeed in this industry by being humble and reliable, or whether you have to be aggressive and cutthroat,” he said. “We’ve chosen the former. And it seems to work.”

Balancing specialism with diversification

Those early years built the foundation. The next step was learning how to grow without losing focus. V7 started as a pure office asset and development manager. “We thought we were doing the right thing, ultra-specialists. One sector. That was our edge.”

Then Covid hit and V7 were heavily exposed to UK institution capital , when redemptions came through, the development tap turned off overnight. V7 was too concentrated which forced them to rethink how they defined focus. The answer wasn’t to go broad, it was to diversify where it made sense. Chris breaks it down simply:

diversify by investor type

diversify by geography

diversify by sector, but only where the skills transfer

They shifted the centre of gravity towards London. “We cut our teeth in the regions, but the real action was always in London. We’ve made big inroads, fifteen schemes now in central London, and we are looking to become London’s pre-eminent developer.”

Industrial followed. “Our investors said, you’re doing a great job on offices, can’t you do that for our industrial assets? We kept politely declining. We were specialists, office only. We didn’t want to become jack of all trades or dilute our specialism.”

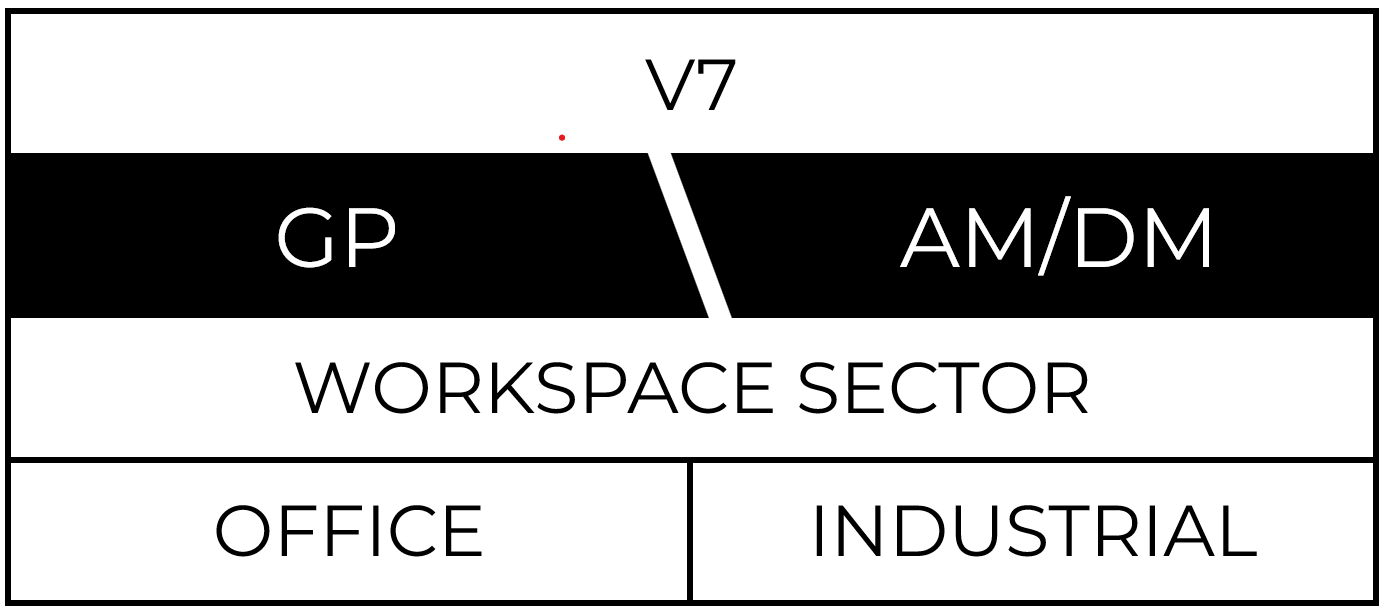

Eventually they did it, but they built the structure to protect the specialism. “We run two separate companies: V7 Office and V7 Industrial - different directors, different teams, different projects. They sit side by side under the same group, but they’re split. That way we keep our depth but still grow across sectors.”

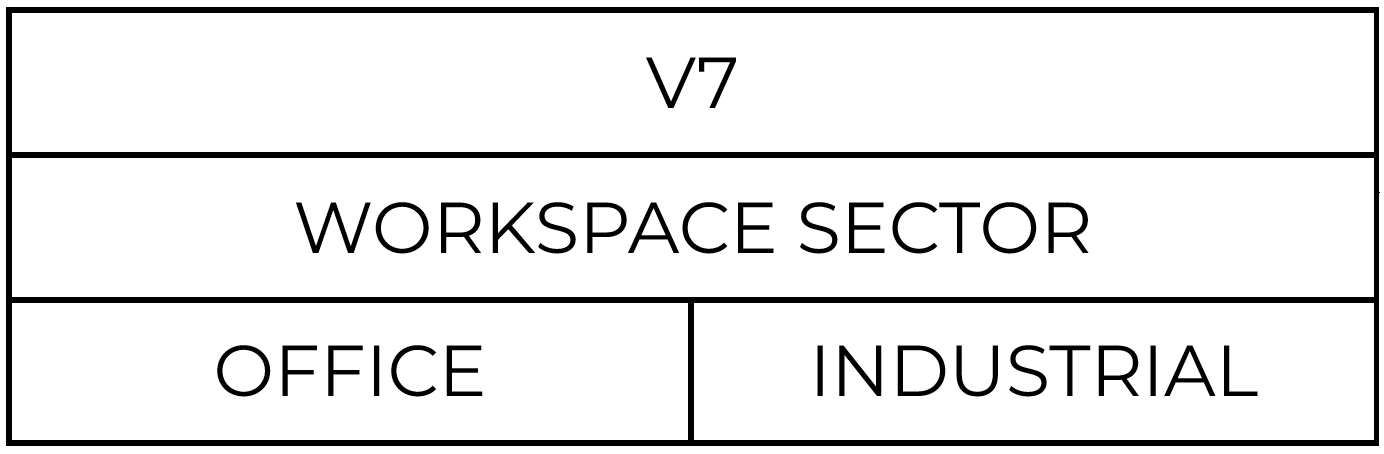

That structure still allows for a clear identity: the workspace sector. Office and industrial complement each other, offices are design-led and cyclical. Industrial’s simpler per building but much more management-heavy. Together, they balance out, leaving a business that looks a bit like this:

Two sides of the business

As the sector mix matured, the business model did too. Alongside the move into industrial, V7 began balancing two types of work: developing its own projects and managing assets for others.

On one side, they buy and co-invest like any developer: find the right partner, the right asset, carry the risk, earn a promote. On the other, they work for existing owners who already hold the building. “That side’s been really successful, when buying is challenging, we can still deliver projects.”

The work itself doesn’t really change. “It’s less glamorous because you’re not running around on the buy side, but it’s the same process. You’re repositioning a building from A to B, just without the acquisition or the disposal. There’s a place for both.”

He sees the balance as practical more than strategic. Real estate never stops moving, leases expire, tenants downsize, owners rethink. “There’s always risk in the system, and where there’s risk, someone needs to offset it. Over the last ten years it’s become more and more acceptable for landlords to bring in external DMs because of specialism.”

That dual model now underpins the business. The development side keeps them entrepreneurial; the management side keeps them active when the market slows. It gives them rhythm and protection in equal measure. “It means we’re always in motion, we’re doing the same work, just from different positions in the capital stack.”

Building on that foundation, we can now add the final two layers that complete the picture of V7:

From deals to strategy

In the early years, V7 were purely deal-driven. “For the first few years, we bought on a deal by deal basis which felt scattergun.”

It was the right approach at the time. “We were developing our track record so we had to be agile. Now we work on individual strategies with investors. We don’t fire random deals at investors, we pre-agree a strategy and then deploy.”

Those partners now range from private equity to family offices. “We prepare an IM, analyse the recent deals and market dynamics, map a pipeline, agree the parameters, and then we deploy, It’s streamlined now. If it doesn’t fit the strategy, we don’t look at it.”

On the office side alone, they run five strategies, from serviced offices to long leasehold, value-add, core-plus, and core.

Building a business that lasts

When I asked how he thinks about the long term, Chris didn't hesitate. "We've got a long term master plan for V7 and an annual business plan that we update every year. You've got to know where you're going. Otherwise you drift."

That planning instinct goes back to the start. "I drew a chart years ago. It was literally on a piece of paper: leasing, investment, asset management, my own business. I stuck it on my fridge. Ten years later, it happened almost exactly as planned."

Most people who succeed in property talk about the deals they've done. Chris talks about systems. V7's model sounds simple: do fewer buildings but do them properly. The difficulty is maintaining that constraint as you grow. It's easier to say yes to more projects, spread thinner, optimise for revenue rather than quality of work. Turning down work that doesn't fit requires either conviction or stubbornness, probably both.

What made them rethink wasn't ambition but necessity. Covid exposed the risk of being too concentrated, heavily in offices, heavily in UK institutions. The response wasn't to abandon focus but to redefine it more carefully: workspace, not just offices. Strategy-led, not deal-driven. Two separate companies to maintain depth while expanding sectors.